In the footsteeps of Matteo Ricci (2)

In the footsteps of Matteo Ricci (2)

The arduous path of tolerance

Shaozhou, south of China, July 1592

Father Matteo Ricci woke up suddenly. What a tug from Father Martines.

—Oooh! You almost ripped my arm off.

—I’m sorry, Father Li Madou. We’re in a very big danger.

Chinese found easier to pronounce Li Madou than Ricci Matteo, in Chinese surname always precedes given name.

—Which danger, Martines?

Father Francesco Martines, formerly Huang Mingshao, was the most faithful and devout novice ever would be. His name was a tribute to a beloved father who had passed away previously.

Matteo Ricci

—Some

evildoers have entered the mission. Father Petris has gone downstairs to parley with them.

—But, our walls are… did you lock last night, Martines?

The walls of the Jesuit mission in Shaozhou were high, so much so that they raised suspicions among the locals.

—I made sure that everything was closed, Father Li Madou. They must have climbed or…

—Or, what?

—Someone has given them stairs to climb.

Puuum.

—What was that, Martines?

—It’s the door to the building.

—The door, indeed.

—So?

—This means they’re inside, Martines.

Blows and moans. Someone comes upstairs.

—It’s them, it’s them, Father Li. We’re going to die.

The door opened wide. It wasn’t the evildoers. It was Father Petris held half unconscious between two lay monks. His head was bleeding.

«Two of ours are killed,» said the lay monk.

Everybody heard them. The mob was coming upstairs.

—Most Holy Mother of God!

Martines put a scary face, all of them put it. Stay calm. Save the people.

—We’ll reach the library through the long corridor. It’s the most protected spot.

It was dark.

—The Tabernacle, Father Li, the Tabernacle. Shall I go, Father?

No, Martines, no. Now we must save ourselves.

Scary steps, the hallway never ends, all Brother monks, one by one. The library. Inside, all of them, at last.

Just closing the library door, the hallway lit up in the background. The torches of the intruders outlined a sinister reflection on the walls. A forest of agitated sticks was approaching like an evil fury.

—Close, soon! Bar the door with these tables!

Boom, boom.

—This door won’t hold for long, Father Li.

—These tables are light. Martines, help me to push them. We´ll use those chairs too. Brothers, got the map and the dictionary, and also as many engravings you can. But save the dictionary first.

The monks took Father Petris through the back door, the map and the dictionary too. This was the first Chinese-Portuguese dictionary in the world. It had taken years of hard work.

—Which engraving do we take, Father?

—The Po-do-lo over the waters. This engraving brings luck.

—What? —a Portuguese Father who was new in the mission asked.

—It’s Peter walking on the waters. Here St. Peter, Petrus, Pedro, is Po-do-lo. It helps a great deal to teach…

Crack, boom. An axe blew up the upper half of the door.

—Oh, my God!

—Martines, make sure these papers reach the governor. They must!

—Oh, Father Li. This writing of yours is very beautiful, a very beautiful calligraphy.

—Do you like it? It’s Treaty on Friendship.

A piece of door got fired rubbing the head.

—No time left, Martines! Take the papers. I’ll hold them with this table.

An axe came out of the shreds of the door. A henchman crawled across the table like a tiger.

—No! My god! Aaaahhh.

Blood shed in the arm. A huge cut left his bare bone.

—I won’t leave you here, Father Li!

—Martines! The papers! Save the papers!

—Brothers have already taken them.

Poor Martines brought his body as a shield. In their blind eagerness to destroy, attackers did not notice the dark robe of Father Martines.

—Let’s take advantage of it. Now, Martines.

—I’ll help you, Father Li.

It was late. The wrongdoer stood and smiled mischievously. At the slight touch of his torch woods and papers started to burn. Smoke. Choking. The exit cut by fire. Martines ran to the window. A thump broke to tatters the slats and the cellophane screen.

—Come on, Father Li, now or never!

No, Martines, No.

Martines took his mentor’s arm and jumped into the void.

—Aaagh!

—Father Li?

—I broke my ankle! You must escape.

—I said I won’t leave you, Father Li. And I won’t.

With great effort, Father Martines grabbed his mentor and started walking.

—Blessed Holy Mother of God!

The assailants were there brandishing their sticks.

—Run by all that’s sacred, Martines.

—I won’t let you, they’d kill you.

They approached very slowly, the prey is trapped. Martines squealed like a madman. His screams made them hessitate. He squealed more, and Father Martines squealed so loud that all evildoers ran away, probably because they feared the scandal might attract the police night patrol. Days later, the magistrate of the prefecture explained that the attack was due to the suspicions that raised those high walls of the mission. Buddhists said that was proof that the Jesuit mission had hidden secrets.

—There are rumors that you and the Portuguese of Macao plotted to invade us —said the magistrate—. Buddhists say that…

—We are not spies, honorable magistrate.

—Father Li.

—No, no, magistrate. We’re monks, just monks.

—What world are you in, Father Li Madou? We’ve suffered drought for years. There are bandits that follow a terrible magician. Don’t you know that Japanese general Hideyoshi Toyotomi has plans to invade Korea, and China too? I still remember the slaughtering the pirates did. And for many of us, the Portuguese are just that: pirates. People would believe anything that made them feel safer. And if you tell them the culprit is hidden behind your walls… they will believe it, because with it they will ascertain where the danger is, and this certainty will calm their spirits.

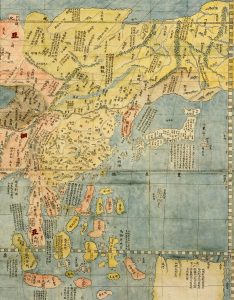

The ringleaders of the mob who had attacked the mission were never found. Fortunately, the papers were saved, including the first Chinese-Portuguese Dictionary of History, the map of Asia and the engraving of Po-do-lo. But of course, Matteo Ricci would walk with a slight limp for the rest of his life.

The Memory Palace

Matteo Ricci (Li Madou) was born in 1552 in Macerata, on the Italian eastern coast. In 1571, Ricci entered as a novice in the Jesuit order of Rome, where he received extensive training in theology, humanities and sciences. He then spent five years learning in Goa (India) and Macao.

Ricci arrived in China in 1583 and fixed his residency in the thriving commercial and administrative centre of Nanchang, Jiangxi province. In 1595, when the mission was attacked, Ricci already mastered Chinese language, he was able to read five hundred ideograms at random and right after repeat them in reverse order. At the end of that year, Ricci would confidently display his brand new language skills writing in Chinese characters a Primer to Friendship, drawn from various classical authors and from the Fathers of the Church. He presented this manuscript to Lu Wanghai, a prince related to the house of Ming, the dynasty that ruled China in those times. The literaty official Prince Lu Wanghai also lived in Nanchang and had already invited him frequently to the banquets he gave in his palace. Lu Wanghai was a man of worth, he had passed the examinations to the top civil service with excellent grades and had acted with distinction in the justice, finance and military administration. Ricci sought to instruct in his study techniques a family at the pinnacle of Chinese society. In his beginnings, Ricci had impressed the literaty elite with his ability to predict eclipses. He took advantage of that and headed to bigger endeavours.

Matteo Ricci and the Astronomy

In 1596, Matteo Ricci taught the Chinese to build a memory palace. The dimensions of the palace depended on how much you want to remember. A small room, a pavilion or a building would create an inner space, a corner in a pavilion, or an altar in a temple, or even a closet or a couch. These palaces, pavilions or sofas were not tangible objects to build materially but mental structures to be kept in the mind. Such spots of memory could be extracted from reality, objects we have been seen with our own eyes and brought to our memory; or they could also be totally fictitious, products of evoked imagination; or they could lay in between, as a building that is perfectly known but with an imaginary door in the back wall or with a mental staircase inside that leads to higher floors that had not existed before. The real purpose of these mental constructions was to offer storage spaces for the myriad of concepts that make up human knowledge. We attribute an image to each thing we want to remember and we locate each one of these images in a spot where it can rest in peace until we are wiling to recall it.

The first memory palaces are attributed to the Greek poet Simonides and Pliny the Elder. In general, Catholics were the ones who believed most in memory. For St. Thomas Aquinas the systems of memory were a branch of ethics rather than just a part of rhetoric. Aquinas considered the importance of having those images of memory in body form, to prevent the spiritual currents from abandoning the soul. Memory was a means to align spiritual intentions, a means to remember heaven and hell. It’s not incidental the detailed description of Hell that Dante makes in The Divine Comedy. Indeed, the memory has also had its detractors: Erasmus, Rabelais, Bacon and, recently, Montserrat Gomendio, Spanish ex-secretary of state of education and significant one of former Spanish Minister of Education Wert.

Matteo Ricci and a scholar

Dangers and violence

The world of Ricci childhood was rife with war and violence. In the streets of his native Macerata people shot one each other and, outside its walls, deserter mercenaries from the wars of the North joined in bands that roamed the fields with total impunity. He also knew of the Battle of Lepanto (1571), Alcazarquivir (1578) or the terrible Spanish siege of Antwerp (1585). Ricci says: «The members of human race cause destruction to each other: they manufacture bloodthirsty instruments capable of cutting hands and feet and separating the limbs from the torso (…) Today people think constantly of new techniques and envision ways to increase the damage they cause. »

In China weapons were banned inside the cities and the civil hierarchy of literaty was above that of the military. This fascinated Ricci: «While among our people, the noblest and bravest becomes a soldier, in China is the most wicked and coward man who he deals with the affairs of War.» For Ricci, Chinese were less warlike than the Europeans. «They use gunpowder not so much for their arquebuses, of which they have few, as for their fireworks displays.»

But although Ricci could seduce the literaty, the violence of the rowdy Macerata of his childhood always pursued him. In his early years in China, he was forced to be present when the victims were whipped. He and other Father once took care of a criminal who had been given eighty blows. The defendant died a month later. Ricci writes: «The victims are beaten in public hearing on the back of the thighs, lying on the ground; they are hit with a stick of the toughest wood possible, the thickness of a finger, four fingers wide, long as two arms extended. The administrators of the punishment hold the stick with the two hands and apply great force, striking either ten, twenty, or thirty blows, showing great cruelty, so much that with the first blow often carries the skin, and with the other blows the meat, piece by piece , of what many people die. »

Year 1605.

—Where is Father Martines? —Ricci asked after arriving from a trip to inland.

—He was arrested three days ago, Father Li —said the lay brother.

—What he did?

—There are rumors that the Spaniards want to invade China from the Philippines. Here it is remembered that two years ago the Spaniards passed twenty thousand Chinese to knife in Manila.

—But Father Martines…

—It seems that the Augustinian Michele Dos Santos reported him.» Father Martines was found to have maps and a book in Portuguese. They consider him a spy.

—God bless! It was me who gave him those things. Let’s go to the police!

—Yes, Father, guards will take you seriously.

—That’s it. We’re going to save Father Martines.

Father Francesco Martines died from the beatings he received in the interrogation and Ricci wept his death with bitterness. Chinese would tell him he looked old. «You put me the Grays,» he would answer. «Frequent dangers, dangers of rivers, dangers of robbers, dangers of those of my race, dangers of the pagan, dangers in the city, dangers in the deserted spots, dangers by sea, dangers between false brothers. »

Matteo Ricci died in 1610. He was granted the privilege of being buried in Chinese soil, and he still rests there.

The tomb of Matteo Ricci in Beijing

Pd. This story uses information from the book «The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci», Jonathan D. Spence, 2002.